William Blake (28 November 1757 – 12 August 1827) was an English poet, painter, and printmaker. Largely unrecognised during his lifetime, Blake is now considered a seminal figure in the history of the poetry and visual arts of the Romantic Age. His prophetic works have been said to form "what is in proportion to its merits the least read body of poetry in the English language". His visual artistry led one contemporary art critic to proclaim him "far and away the greatest artist Britain has ever produced". In 2002, Blake was placed at number 38 in the BBC's poll of the 100 Greatest Britons. Although he lived in London his entire life (except for three years spent in Felpham), he produced a diverse and symbolically rich œuvre, which embraced the imagination as "the body of God" or "human existence itself".

Although Blake was considered mad by contemporaries for his idiosyncratic views, he is held in high regard by later critics for his expressiveness and creativity, and for the philosophical and mystical undercurrents within his work. His paintings and poetry have been characterised as part of the Romantic movement and as "Pre-Romantic". Reverent of the Bible but hostile to the Church of England (indeed, to almost all forms of organised religion), Blake was influenced by the ideals and ambitions of the French and American Revolutions. Though later he rejected many of these political beliefs, he maintained an amiable relationship with the political activist Thomas Paine; he was also influenced by thinkers such as Emanuel Swedenborg. Despite these known influences, the singularity of Blake's work makes him difficult to classify. The 19th-century scholar William Rossetti characterised him as a "glorious luminary", and "a man not forestalled by predecessors, nor to be classed with contemporaries, nor to be replaced by known or readily surmisable successors".

William Blake was born on 28 November 1757 at 28 Broad Street (now Broadwick St.) in Soho, London. He was the third of seven children, two of whom died in infancy. Blake's father, James, was a hosier. He attended school only long enough to learn reading and writing, leaving at the age of ten, and was otherwise educated at home by his mother Catherine Blake (née Wright). Even though the Blakes were English Dissenters, William was baptised on 11 December at St James's Church, Piccadilly, London. The Bible was an early and profound influence on Blake, and remained a source of inspiration throughout his life.

Blake started engraving copies of drawings of Greek antiquities purchased for him by his father, a practice that was preferred to actual drawing. Within these drawings Blake found his first exposure to classical forms through the work of Raphael, Michelangelo, Maarten van Heemskerck and Albrecht Dürer. The number of prints and bound books that James and Catherine were able to purchase for young William suggests that the Blakes enjoyed, at least for a time, a comfortable wealth. When William was ten years old, his parents knew enough of his headstrong temperament that he was not sent to school but instead enrolled in drawing classes at Pars's drawing school in the Strand. He read avidly on subjects of his own choosing. During this period, Blake made explorations into poetry; his early work displays knowledge of Ben Jonson, Edmund Spenser, and the Psalms.

On 4 August 1772, Blake was apprenticed to engraver James Basire of Great Queen Street, at the sum of £52.10, for a term of seven years. At the end of the term, aged 21, he became a professional engraver. No record survives of any serious disagreement or conflict between the two during the period of Blake's apprenticeship, but Peter Ackroyd's biography notes that Blake later added Basire's name to a list of artistic adversaries – and then crossed it out. This aside, Basire's style of line-engraving was of a kind held at the time to be old-fashioned compared to the flashier stipple or mezzotint styles. It has been speculated that Blake's instruction in this outmoded form may have been detrimental to his acquiring of work or recognition in later life.

After two years, Basire sent his apprentice to copy images from the Gothic churches in London (perhaps to settle a quarrel between Blake and James Parker, his fellow apprentice). His experiences in Westminster Abbey helped form his artistic style and ideas. The Abbey of his day was decorated with suits of armour, painted funeral effigies and varicoloured waxworks. Ackroyd notes that "...the most immediate would have been of faded brightness and colour". This close study of the Gothic (which he saw as the "living form") left clear traces in his style. In the long afternoons Blake spent sketching in the Abbey, he was occasionally interrupted by boys from Westminster School, who were allowed in the Abbey. They teased him and one tormented him so much that Basire knocked the boy off a scaffold to the ground, "upon which he fell with terrific Violence". After Basire complained to the Dean, the schoolboys' privilege was withdrawn. Blake experienced visions in the Abbey, he saw Christ and his Apostles and a great procession of monks and priests and heard their chant.

On 8 October 1779, Blake became a student at the Royal Academy in Old Somerset House, near the Strand. While the terms of his study required no payment, he was expected to supply his own materials throughout the six-year period. There, he rebelled against what he regarded as the unfinished style of fashionable painters such as Rubens, championed by the school's first president, Joshua Reynolds. Over time, Blake came to detest Reynolds' attitude towards art, especially his pursuit of "general truth" and "general beauty". Reynolds wrote in his Discourses that the "disposition to abstractions, to generalising and classification, is the great glory of the human mind"; Blake responded, in marginalia to his personal copy, that "To Generalize is to be an Idiot; To Particularize is the Alone Distinction of Merit". Blake also disliked Reynolds' apparent humility, which he held to be a form of hypocrisy. Against Reynolds' fashionable oil painting, Blake preferred the Classical precision of his early influences, Michelangelo and Raphael.

David Bindman suggests that Blake's antagonism towards Reynolds arose not so much from the president's opinions (like Blake, Reynolds held history painting to be of greater value than landscape and portraiture), but rather "against his hypocrisy in not putting his ideals into practice." Certainly Blake was not averse to exhibiting at the Royal Academy, submitting works on six occasions between 1780 and 1808.

Blake became a friend of John Flaxman, Thomas Stothard and George Cumberland during his first year at the Royal Academy. They shared radical views, with Stothard and Cumberland joining the Society for Constitutional Information.

Blake's first biographer, Alexander Gilchrist, records that in June 1780 Blake was walking towards Basire's shop in Great Queen Street when he was swept up by a rampaging mob that stormed Newgate Prison. The mob attacked the prison gates with shovels and pickaxes, set the building ablaze, and released the prisoners inside. Blake was reportedly in the front rank of the mob during the attack. The riots, in response to a parliamentary bill revoking sanctions against Roman Catholicism, became known as the Gordon Riots and provoked a flurry of legislation from the government of George III, and the creation of the first police force.

Blake met Catherine Boucher in 1782 when he was recovering from a relationship that had culminated in a refusal of his marriage proposal. He recounted the story of his heartbreak for Catherine and her parents, after which he asked Catherine, "Do you pity me?" When she responded affirmatively, he declared, "Then I love you." Blake married Catherine – who was five years his junior – on 18 August 1782 in St Mary's Church, Battersea. Illiterate, Catherine signed her wedding contract with an X. The original wedding certificate may be viewed at the church, where a commemorative stained-glass window was installed between 1976 and 1982. Later, in addition to teaching Catherine to read and write, Blake trained her as an engraver. Throughout his life she proved an invaluable aid, helping to print his illuminated works and maintaining his spirits throughout numerous misfortunes.

Blake's first collection of poems, Poetical Sketches, was printed around 1783. After his father's death, Blake and former fellow apprentice James Parker opened a print shop in 1784, and began working with radical publisher Joseph Johnson. Johnson's house was a meeting-place for some leading English intellectual dissidents of the time: theologian and scientist Joseph Priestley, philosopher Richard Price, artist John Henry Fuseli, early feminist Mary Wollstonecraft and English-American revolutionary Thomas Paine. Along with William Wordsworth and William Godwin, Blake had great hopes for the French and American revolutions and wore a Phrygian cap in solidarity with the French revolutionaries, but despaired with the rise of Robespierre and the Reign of Terror in France. In 1784 Blake composed his unfinished manuscript An Island in the Moon.

Blake illustrated Original Stories from Real Life (2nd edition, 1791) by Mary Wollstonecraft. They seem to have shared some views on sexual equality and the institution of marriage, but there is no evidence proving without doubt that they actually met. In 1793's Visions of the Daughters of Albion, Blake condemned the cruel absurdity of enforced chastity and marriage without love and defended the right of women to complete self-fulfilment.

From 1790 to 1800, William Blake lived in North Lambeth, London, at 13 Hercules Buildings, Hercules Road. The property was demolished in 1918, but the site is now marked with a plaque. There is a series of 70 mosaics inspired by Blake in the nearby railway tunnels of Waterloo Station.

In 1788, aged 31, Blake experimented with relief etching, a method he used to produce most of his books, paintings, pamphlets and poems. The process is also referred to as illuminated printing, and the finished products as illuminated books or prints. Illuminated printing involved writing the text of the poems on copper plates with pens and brushes, using an acid-resistant medium. Illustrations could appear alongside words in the manner of earlier illuminated manuscripts. He then etched the plates in acid to dissolve the untreated copper and leave the design standing in relief (hence the name).

This is a reversal of the usual method of etching, where the lines of the design are exposed to the acid, and the plate printed by the intaglio method. Relief etching (which Blake referred to as "stereotype" in The Ghost of Abel) was intended as a means for producing his illuminated books more quickly than via intaglio. Stereotype, a process invented in 1725, consisted of making a metal cast from a wood engraving, but Blake's innovation was, as described above, very different. The pages printed from these plates were hand-coloured in water colours and stitched together to form a volume. Blake used illuminated printing for most of his well-known works, including Songs of Innocence and of Experience, The Book of Thel, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell and Jerusalem.

Although Blake has become most famous for his relief etching, his commercial work largely consisted of intaglio engraving, the standard process of engraving in the 18th century in which the artist incised an image into the copper plate, a complex and laborious process, with plates taking months or years to complete, but as Blake's contemporary, John Boydell, realised, such engraving offered a "missing link with commerce", enabling artists to connect with a mass audience and became an immensely important activity by the end of the 18th century.

Blake employed intaglio engraving in his own work, most notably for the illustrations of the Book of Job, completed just before his death. Most critical work has concentrated on Blake's relief etching as a technique because it is the most innovative aspect of his art, but a 2009 study drew attention to Blake's surviving plates, including those for the Book of Job: they demonstrate that he made frequent use of a technique known as "repoussage", a means of obliterating mistakes by hammering them out by hitting the back of the plate. Such techniques, typical of engraving work of the time, are very different to the much faster and fluid way of drawing on a plate that Blake employed for his relief etching, and indicates why the engravings took so long to complete.

Blake's marriage to Catherine was close and devoted until his death. Blake taught Catherine to write, and she helped him colour his printed poems. Gilchrist refers to "stormy times" in the early years of the marriage. Some biographers have suggested that Blake tried to bring a concubine into the marriage bed in accordance with the beliefs of the more radical branches of the Swedenborgian Society, but other scholars have dismissed these theories as conjecture. William and Catherine's first daughter and last child might be Thel described in The Book of Thel who was conceived as dead.

In 1800, Blake moved to a cottage at Felpham, in Sussex (now West Sussex), to take up a job illustrating the works of William Hayley, a minor poet. It was in this cottage that Blake began Milton (the title page is dated 1804, but Blake continued to work on it until 1808). The preface to this work includes a poem beginning "And did those feet in ancient time", which became the words for the anthem "Jerusalem". Over time, Blake began to resent his new patron, believing that Hayley was uninterested in true artistry, and preoccupied with "the meer drudgery of business" (E724). Blake's disenchantment with Hayley has been speculated to have influenced Milton: a Poem, in which Blake wrote that "Corporeal Friends are Spiritual Enemies". (4:26, E98)

Blake's trouble with authority came to a head in August 1803, when he was involved in a physical altercation with a soldier, John Schofield. Blake was charged not only with assault, but with uttering seditious and treasonable expressions against the king. Schofield claimed that Blake had exclaimed "Damn the king. The soldiers are all slaves." Blake was cleared in the Chichester assizes of the charges. According to a report in the Sussex county paper, "The invented character of was ... so obvious that an acquittal resulted". Schofield was later depicted wearing "mind forged manacles" in an illustration to Jerusalem.

Blake returned to London in 1804 and began to write and illustrate Jerusalem (1804–20), his most ambitious work. Having conceived the idea of portraying the characters in Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, Blake approached the dealer Robert Cromek, with a view to marketing an engraving. Knowing Blake was too eccentric to produce a popular work, Cromek promptly commissioned Blake's friend Thomas Stothard to execute the concept. When Blake learned he had been cheated, he broke off contact with Stothard. He set up an independent exhibition in his brother's haberdashery shop at 27 Broad Street in Soho. The exhibition was designed to market his own version of the Canterbury illustration (titled The Canterbury Pilgrims), along with other works. As a result, he wrote his Descriptive Catalogue (1809), which contains what Anthony Blunt called a "brilliant analysis" of Chaucer and is regularly anthologised as a classic of Chaucer criticism. It also contained detailed explanations of his other paintings. The exhibition was very poorly attended, selling none of the temperas or watercolours. Its only review, in The Examiner, was hostile.

Also around this time (circa 1808), Blake gave vigorous expression of views on art in an extensive series of polemical annotations to the Discourses of Sir Joshua Reynolds, denouncing the Royal Academy as a fraud and proclaiming, "To Generalize is to be an Idiot".

In 1818, he was introduced by George Cumberland's son to a young artist named John Linnell. A blue plaque commemorates Blake and Linnell at Old Wyldes' at North End, Hampstead. Through Linnell he met Samuel Palmer, who belonged to a group of artists who called themselves the Shoreham Ancients. The group shared Blake's rejection of modern trends and his belief in a spiritual and artistic New Age. Aged 65, Blake began work on illustrations for the Book of Job, later admired by Ruskin, who compared Blake favourably to Rembrandt, and by Vaughan Williams, who based his ballet Job: A Masque for Dancing on a selection of the illustrations.

In later life Blake began to sell a great number of his works, particularly his Bible illustrations, to Thomas Butts, a patron who saw Blake more as a friend than a man whose work held artistic merit; this was typical of the opinions held of Blake throughout his life.

The commission for Dante's Divine Comedy came to Blake in 1826 through Linnell, with the aim of producing a series of engravings. Blake's death in 1827 cut short the enterprise, and only a handful of watercolours were completed, with only seven of the engravings arriving at proof form. Even so, they have evoked praise:

'The Dante watercolours are among Blake's richest achievements, engaging fully with the problem of illustrating a poem of this complexity. The mastery of watercolour has reached an even higher level than before, and is used to extraordinary effect in differentiating the atmosphere of the three states of being in the poem'.

Blake's illustrations of the poem are not merely accompanying works, but rather seem to critically revise, or furnish commentary on, certain spiritual or moral aspects of the text.

Because the project was never completed, Blake's intent may be obscured. Some indicators bolster the impression that Blake's illustrations in their totality would take issue with the text they accompany: In the margin of Homer Bearing the Sword and His Companions, Blake notes, "Every thing in Dantes Comedia shews That for Tyrannical Purposes he has made This World the Foundation of All & the Goddess Nature & not the Holy Ghost." Blake seems to dissent from Dante's admiration of the poetic works of ancient Greece, and from the apparent glee with which Dante allots punishments in Hell (as evidenced by the grim humour of the cantos).

At the same time, Blake shared Dante's distrust of materialism and the corruptive nature of power, and clearly relished the opportunity to represent the atmosphere and imagery of Dante's work pictorially. Even as he seemed to be near death, Blake's central preoccupation was his feverish work on the illustrations to Dante's Inferno; he is said to have spent one of the very last shillings he possessed on a pencil to continue sketching.

Blake's last years were spent at Fountain Court off the Strand (the property was demolished in the 1880s, when the Savoy Hotel was built). On the day of his death (12 August 1827), Blake worked relentlessly on his Dante series. Eventually, it is reported, he ceased working and turned to his wife, who was in tears by his bedside. Beholding her, Blake is said to have cried, "Stay Kate! Keep just as you are – I will draw your portrait – for you have ever been an angel to me." Having completed this portrait (now lost), Blake laid down his tools and began to sing hymns and verses. At six that evening, after promising his wife that he would be with her always, Blake died. Gilchrist reports that a female lodger in the house, present at his expiration, said, "I have been at the death, not of a man, but of a blessed angel."

George Richmond gives the following account of Blake's death in a letter to Samuel Palmer:

He died ... in a most glorious manner. He said He was going to that Country he had all His life wished to see & expressed Himself Happy, hoping for Salvation through Jesus Christ – Just before he died His Countenance became fair. His eyes Brighten'd and he burst out Singing of the things he saw in Heaven.

Catherine paid for Blake's funeral with money lent to her by Linnell. He was buried five days after his death – on the eve of his 45th wedding anniversary – at the Dissenter's burial ground in Bunhill Fields, in what is today in the Borough of Islington, London. His parents were interred in the same grounds. Present at the ceremonies were Catherine, Edward Calvert, George Richmond, Frederick Tatham and John Linnell. Following Blake's death, Catherine moved into Tatham's house as a housekeeper. She believed she was regularly visited by Blake's spirit. She continued selling his illuminated works and paintings, but entertained no business transaction without first "consulting Mr. Blake". On the day of her death, in October 1831, she was as calm and cheerful as her husband, and called out to him "as if he were only in the next room, to say she was coming to him, and it would not be long now".

On her death, Blake's manuscripts were inherited by Frederick Tatham, who burned some he deemed heretical or politically radical. Tatham was an Irvingite, one of the many fundamentalist movements of the 19th century, and opposed to any work that smacked of blasphemy. John Linnell erased sexual imagery from a number of Blake's drawings.

Since 1965, the exact location of William Blake's grave had been lost and forgotten as gravestones were taken away to create a lawn. Blake’s grave is commemorated by a stone that reads "Near by lie the remains of the poet-painter William Blake 1757–1827 and his wife Catherine Sophia 1762–1831". The memorial stone is situated approximately 20 metres away from the actual grave, which is not marked. Members of the group Friends of William Blake have rediscovered the location and intend to place a permanent memorial at the site.

Blake is recognised as a saint in the Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica. The Blake Prize for Religious Art was established in his honour in Australia in 1949. In 1957 a memorial to Blake and his wife was erected in Westminster Abbey.

THE NIGHT OF ENITHARMON'S JOY

William Blake (c1795)

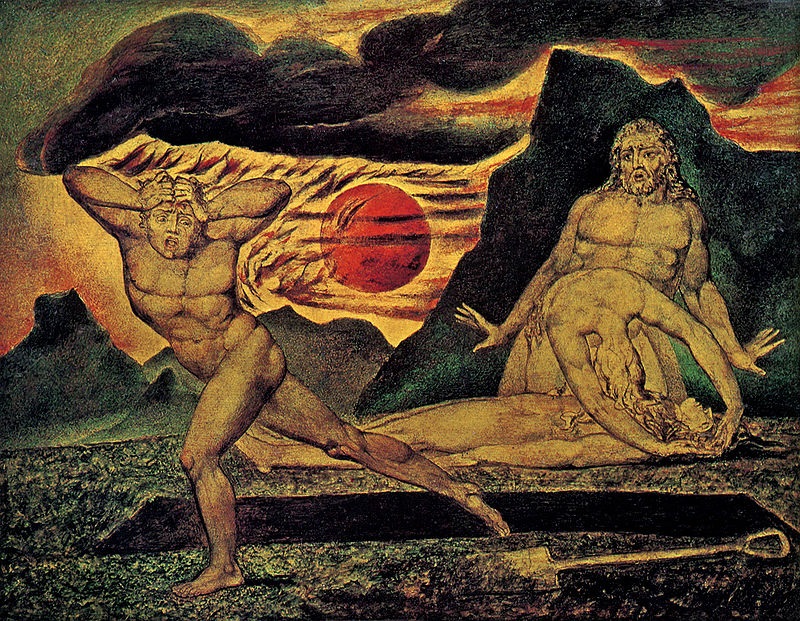

THE BODY OF ABEL FOUND BY ADAM AND EVE

William Blake (c1825)

SIR ISAAC NEWTON

William Blake (c1804)

THE GHOST OF A FLEA

William Blake (c1819-c1820)

NEBUCHADNEZZAR

William Blake (c1795-c1805)

THE ACIENT OF DAYS SETTING A COMPASS TO THE EARTH

William Blake (c1794)