Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12% tin and often with the addition of other metals (such as aluminium, manganese, nickel or zinc) and sometimes non-metals or metalloids such as arsenic, phosphorus or silicon. These additions produce a range of alloys that may be harder than copper alone, or have other useful properties, such as stiffness, ductility or machinability. The historical period where the archeological record contains many bronze artifacts is known as the Bronze Age.

Because historical pieces were often made of brasses (copper and zinc) and bronzes with different compositions, modern museum and scholarly descriptions of older objects increasingly use the more inclusive term "copper alloy" instead.

Italian bronze

Neptune brandishing his trident, upon two sea-horses - a Venetian bronze knocker of the 16th century By the 12th century the Italian craftsmen had developed a style of their own, as may be seen in the bronze doors of Saint Zeno, Verona (which are made of hammered and not cast bronze), Ravello, Trani and Monreale. Bonanno da Pisa made a series of doors for the duomo of that city, one pair of which remains. The 14th century witnessed the birth of a great revival in the working of bronze, which was destined to flourish for at least four centuries. Bronze was a metal beloved of the Italian craftsman; in that metal he produced objects for every conceivable purpose, great or small, from a door-knob to the mighty doors by Lorenzo Ghiberti at Florence, of which Michelangelo remarked that they would stand well at the gates of Paradise. Nicola, Giovanni and Andrea Pisano, Ghiberti, Brunelleschi, Donatello, Verrocchio, Cellini, Michelangelo, Giovanni da Bologna — these and many others produced great works in bronze. Benedetto da Rovezzano came to England in 1524 to execute a tomb for Cardinal Wosley, part of which, after many vicissitudes, is now in the crypt of St Paul's Cathedral. Pietro Torrigiano of Florence executed the tomb of Henry VII in Westminster Abbey. Alessandro Leopardi, at the beginning of the 16th century, completed the three admirable sockets for flag-staffs which still adorn the Piazza San Marco, Venice. A further development showed itself in the production of portrait medals in bronze, which reached a high degree of perfection and engaged the attention of many celebrated artists. Bronze plaquettes for the decoration of large objects exhibit a fine sense of design and composition. Of smaller objects, for church and domestic use, the number was legion. Among the former may be mentioned crucifixes, shrines, altar and paschal candlesticks, such as the elaborate examples at the Certosa of Pavia; for secular use, mortars, inkstands, candlesticks and a large number of splendid door-knockers and handles, all executed with consummate skill and perfection of finish. Work of this kind continued to be made throughout the 17th and 18th centuries.

Italian Sculptors;

Jacopo della Quercia (c.1374–1438)

Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378–1455)

Nanni di Banco (c.1384–1421)

Donatello (c.1386–1466)

Luca della Robbia (1399/1400–1482)

Bernardo Rossellino (1409–1464)

Vecchietta (1410–1480)

Agostino di Duccio (1418–1481)

Domenico Gagini (1420–1492)

Mino da Fiesole (c.1429–1484)

Francesco Laurana (c.1430–1502)

Desiderio da Settignano (c.1430–1464)

Andrea della Robbia (1435–1525)

Niccolò dell'Arca (c.1435/1440–1494)

Benedetto da Maiano (1442–1497)

Giovanni Antonio Amadeo (c.1447–1522)

Tullio Lombardo (1460–1532)

Andrea Sansovino (c.1467–1529)

Pietro Torrigiano (1472–1528)

Michelangelo (1475–1564)

Bartolommeo Bandinelli (1493–1560)

Benvenuto Cellini (1500–1571)

Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli (c.1506–1563)

Leone Leoni (1509–1590)

Bartolomeo Ammanati (1511–1592)

Alessandro Vittoria (1525–1608)

Giambologna (1529–1608)

Vincenzo Danti (1530–1576)

Stefano Maderno (c.1576–1636)

Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680)

Giovanni Battista Foggini (1652–1725)

Giuseppe Sanmartino (1720–1793)

Antonio Canova (1757–1822)

Lorenzo Bartolini (1777–1850)

Vincenzo Gemito (1852–1929)

Umberto Boccioni (1882–1916)

Arturo Martini (1889–1947)

Marino Marini (1901–1980)

Giacomo Manzù (1908–1991)

Silvio Gazzaniga (1921-)

Arnaldo Pomodoro (1926-)

French bronze

Patinated and ormolu Empire timepiece representing Mars and Venus, an allegory of the wedding of Napoleon I and Archduchess Marie Louise of Austria in 1810. By the famous bronzier Pierre-Philippe Thomire, ca. 1810.

The Candelabro Trivulzio in the Milan Cathedral, a seven-branch bronze candlestick measuring 5 meters in height, has a base and lower part decorated with intricately designed ornament which is considered by many to be French work of the 13th century; the upper part with the branches was added in the second half of the 16th century. A portion of a similar object showing the same intricate decoration existed formerly at Reims, but was unfortunately destroyed during World War I.

In the 16th century the names of Germain Pilon and Jean Goujon are sufficient evidence of the ability to work in bronze. A great outburst of artistic energy is seen from the beginning of the 17th century, when works in ormolu or gilt bronze were produced in huge quantities. The craftsmanship is magnificent and of the highest quality, the designs at first refined and symmetrical; but later, under the influence of the rococo style, introduced in 1723, aiming only at gorgeous magnificence. It was all in keeping with the spirit of the age, and in their own sumptuous setting these fine candelabra, sconces, vases, clocks and rich mountings of furniture are entirely harmonious. The "ciseleur" and the "fondeur", such as Pierre Gouthière and Jacques Caffieri, associated themselves with the makers of fine furniture and of delicate Sèvres porcelain, the result being extreme richness and handsome effect. The style was succeeded after the French Revolution by a stiff, classical manner which, although having a charm of its own, lacks the life and freedom of earlier work. In London the styles may be studied in the Wallace collection, Manchester Square, and at the Victoria and Albert Museum, South Kensington; in New York at the Metropolitan Museum.

French Sculptors;

Pierre Bontemps (c.1505-1568)

Jean Goujon (c.1510-1565)

Jean Juste (c.1515-1530)

Pierre Lescot (c.1515-1578)

Germain Pilon (c.1535-1590)

Barthélemy Prieur (c.1536-1611)

Antoine Coysevox (1640-1720)

Nicolas Coustou (1658–1733)

Antoine Coypel (1661–1722)

Louis-François Roubiliac (1702–1762)

Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne (1704–1778)

Jean-Baptiste Pigalle (1714–1785)

Etienne-Maurice Falconet (1716–1791)

Jean-Baptiste Defernex (1729–1783)

Jean Antoine Houdon (1741–1828)

François Rude (1784–1855)

Antoine-Louis Barye (1795–1875)

Auguste Préault (1809–1879)

Eugène André Oudiné (1810–1875)

Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse (1824–1887)

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (1827–1875)

Edgar Degas (1834–1917)

Auguste Rodin (1840–1917)

Jean Antonin Mercié (1845–1916)

Paul Gauguin (1848–1903)

Antoine Bourdelle (1861–1929)

Aristide Maillol (1861–1944)

Georges Lacombe (1868–1916)

Constantin Brâncuși (1876–1957)

Raymond Duchamp-Villon (1876–1918)

Jean (Hans) Arp (1886–1966)

Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968)

Ossip Zadkine (1890–1967)

Jacques Lipchitz (1891–1973)

Max Ernst (1891–1976)

Georges Gimel (1898–1962)

Alberto Giacometti (1901–1966)

Hans Bellmer (1902–1975)

Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010)

Etienne Martin (1913–1995)

Constantine Andreou (1917–2007)

César Baldaccini (1921–1998)

Jean Tinguely (1925–1991)

Armand Fernandez (1928–2005)

Niki de Saint-Phalle (1930–2002)

Jules Michel (1931–)

Jean-Michel Sanejouand (1934–)

Daniel Buren (1938–)

Andrey Lekarski (1940–)

Christian Boltanski (1944–)

Jean-Yves Lechevallier (1946-)

Gérard Garouste (1946–)

Pierre Toutain-Dorbec (1951–)

Jean-Marc Bustamante (1952–)

Jean Paul Leon (1955–)

Pascale Fournier (1951–)

Patrick Moya (1955–)

Michel De Caso (1956–)

Amelie Chabannes (1974–)

Abdelkader Benchamma (1975–)

English bronze

Casting in bronze reached high perfection in England, where a number of monuments yet remain. William Torel, goldsmith and citizen of London, made a bronze effigy og Henry III, and later that of Queen Eleanor for their tombs in Westminster Abbey; the effigy of Edward III was probably the work of one of his pupils. No bronze fonts are found in English churches, but a number of processional crucifixes have survived from the 15th century, all following the same design and of crude execution. Sanctuary rings or knockers exist at Norwich, Gloucester and elsewhere; the most remarkable is that on the north door of the nave of Durham Cathedral which has sufficient character of its own to differentiate it from its Continental brothers and to suggest a Northern origin. The Gloucester Candlestick in the Victoria and Albert Museum in South Kensington, displays the power and imagination of the designer as well as an extraordinary manipulative skill on the part of the founder. According to an inscription on the object, this candlestick, which stands some 2 ft (61 cm) high and is made of an alloy allied to bronze, was made for Abbot Peter who ruled from 1109 to 1112. While the outline is carefully preserved, the ornament consists of a mass of figures of monsters, birds and men, mixed and intertwined to the verge of confusion. As a piece of casting it is a triumph of technical ability. For secular use the mortar was one of the commonest of objects in England as on the Continent; early examples of Gothic design are of great beauty. In later examples a mixture of styles is found in the bands of Gothic and Renaissance ornament, which are freely used in combination. Bronze ewers must have been common; of the more ornate kind two may be seen, one at South Kensington and a second at the British Museum. These are large vessels of about 2 ft (61 cm) in height, with shields of arms and inscriptions in bell-founders' lettering. Many objects for domestic use, such as mortars, skillets, etc., were produced in later centuries.

European brass and bronze

This section is not concerned with sculpture in bronze, but rather with the many artistic applications of the metal in connection with architecture, or with objects for ecclesiastical and domestic use. Why bronze was preferred in Italy, iron in Spain and Germany and brass in the Low Countries cannot be satisfactorily determined; national temperamente is impressed on the choice of metals and also on the methods of working them. Centres of artistic energy shift from one place to another owing to wars, conquests or migrations.

Leaving alone remote antiquity and starting with Imperial Rome, the working of bronze, inspired probably by conquered Greece, is clearly seen. There are ancient bronze doors in the Temple of Romulus in the Roman Forum; others from the baths of Caracalla are in the Lateran Basilica, which also contains four fine gilt bronze fluted columns of the Corinthian order. The Naples Museum contains a large collection of domestic utensils of bronze, recovered from the buried towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum, which show a high degree of perfection in the working of the metal, as well as a wide application of its use. A number of moorings in the form of finely modelled animal heads, made in the 1st century AD, and recovered from Lake Nemi in the Alban hills some years ago, show a further acquaintance with the skilful working of this metal. The throne of Dagobert in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, appears to be a Roman bronze curule chair, with back and part of the arms added by the Abbot Suger in the 12th century.

Byzantium, from the time when Constantine made it the seat of empire, in the early part of the 4th century, was for 1,000 years renowned for its works in metal. Its position as a trade centre between East and West attracted all the finest work provided by the artistic skills of craftsmen from Syria, Egypt, Persia, Asia Minor and the northern shores of the Black Sea, and for 400 years, until the beginning of the Iconoclastic period in the first half of the 8th century, its output was enormous. Several Italian churches still retain bronze doors cast in Constantinople in the later days of the Eastern Empire, such as those presented by the members of the Pantaleone family, in the latter half of the 11th century, to the churches at Amalfi, Monte Cassino, Atrani and Monte Gargano. Similar doors are at Salerno; and St Mark's, Venice, also has doors of Greek origin.

The period of the Iconoclasts fortunately synchronised with the reign of Charlemagne, whose power was felt throughout western Europe. The craftsmen who were forced to leave Byzantium were welcomed by him in his capitals of Cologne and Aix-la-Chapelle and their influence was also felt in France. Another stream passed by way of the Mediterranean to Italy, where the old classical art had decayed owing to the many national calamities, and here it brought about a revival. In the Rhineland the terms "Rhenish-Byzantine" and "Romanesque" applied to architecture and works of art generally, testify to the provenance of the style of this and the succeeding period. The bronze doors of the Cathedral of Aix-la-Chapelle are of classic design and date probably from Charlemagne's time. All through the Middle Ages the use of bronze continued on a great scale, particularly in the 11th and 12th centuries. Bernward, bishop of Hildesheim, a great patron of the arts, had bronze doors, the Bernward Doors, made for St Nicholas' church (afterwards removed to the cathedral) which were set up in 1015; great doors were made for Augsburg somewhere between 1060 and 1065, and for Mainz shortly after the year 1000. A prominent feature on several of these doors is seen in finely modelled lion jaws, with conventional manes and with ring hanging from their jaws. These have their counterpart in France and Scandinavia as well as in England, where they are represented by the so-called Sanctuary Knocker at Durham Cathedral.

Provision of elaborate tomb monuments and of church furniture gave much work to the German founder, the former largely in the nature of sculpture. Mention may be made of the seven-branch candlestick at Essen Cathedral made for the Abbess Matilda about the year 1000, and another at Brunswick completed in 1223; also of the remarkable font of the 13th century made for Hildesheim Cathedral at the charge of Wilbernus, a canon of the cathedral. Other fonts are found at Brandenburg and Würzburg. Of smaller objects such as ewers, holy-water vessels, reliquaries and candelabra, a vast number were produced. Most of the finest work of the 15th century was executed for the Church.

The end of the Gothic period in Germany found the great craftsman, Peter Vischer of Nuremberg, and his sons, working on the bronze shrine to contain the reliquary of Saint Sebald, a finely conceived monument of architectural form, with rich details of ornament and figures; among the latter appearing the artist in his working dress. The shrine was completed and set up in the year 1516. This great craftsman executed other fine works at Magdeburg, Römhild and Breslau. Reference should be made to the colossal monument at Innsbruck, the tomb of the Emperor Maximilian I, with its 28 bronze statues of more than life size. Large fountains in which bronze was freely employed were set up, such as those at Munich and Augsburg. The tendency was to use this metal for large works of an architectural or sculpturesque nature; while at the same time smaller objects were produced for domestic purposes.

Bronze articles are always present in Fine Furnishings and Decorated Arts auctions at Centurion Auctioneers which are held regularly.

Click on the images for more information.

Should you have any questions in regards to Bronze articles that you might wish to evaluate or to list in future auctions, please visit the CONTACT page , the VALUATIONS page or the REQUEST INFORMATION page or send an email to Centurion Auctioneers - info@centurion-auctions.com

Because historical pieces were often made of brasses (copper and zinc) and bronzes with different compositions, modern museum and scholarly descriptions of older objects increasingly use the more inclusive term "copper alloy" instead.

Italian bronze

Neptune brandishing his trident, upon two sea-horses - a Venetian bronze knocker of the 16th century By the 12th century the Italian craftsmen had developed a style of their own, as may be seen in the bronze doors of Saint Zeno, Verona (which are made of hammered and not cast bronze), Ravello, Trani and Monreale. Bonanno da Pisa made a series of doors for the duomo of that city, one pair of which remains. The 14th century witnessed the birth of a great revival in the working of bronze, which was destined to flourish for at least four centuries. Bronze was a metal beloved of the Italian craftsman; in that metal he produced objects for every conceivable purpose, great or small, from a door-knob to the mighty doors by Lorenzo Ghiberti at Florence, of which Michelangelo remarked that they would stand well at the gates of Paradise. Nicola, Giovanni and Andrea Pisano, Ghiberti, Brunelleschi, Donatello, Verrocchio, Cellini, Michelangelo, Giovanni da Bologna — these and many others produced great works in bronze. Benedetto da Rovezzano came to England in 1524 to execute a tomb for Cardinal Wosley, part of which, after many vicissitudes, is now in the crypt of St Paul's Cathedral. Pietro Torrigiano of Florence executed the tomb of Henry VII in Westminster Abbey. Alessandro Leopardi, at the beginning of the 16th century, completed the three admirable sockets for flag-staffs which still adorn the Piazza San Marco, Venice. A further development showed itself in the production of portrait medals in bronze, which reached a high degree of perfection and engaged the attention of many celebrated artists. Bronze plaquettes for the decoration of large objects exhibit a fine sense of design and composition. Of smaller objects, for church and domestic use, the number was legion. Among the former may be mentioned crucifixes, shrines, altar and paschal candlesticks, such as the elaborate examples at the Certosa of Pavia; for secular use, mortars, inkstands, candlesticks and a large number of splendid door-knockers and handles, all executed with consummate skill and perfection of finish. Work of this kind continued to be made throughout the 17th and 18th centuries.

Italian Sculptors;

Jacopo della Quercia (c.1374–1438)

Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378–1455)

Nanni di Banco (c.1384–1421)

Donatello (c.1386–1466)

Luca della Robbia (1399/1400–1482)

Bernardo Rossellino (1409–1464)

Vecchietta (1410–1480)

Agostino di Duccio (1418–1481)

Domenico Gagini (1420–1492)

Mino da Fiesole (c.1429–1484)

Francesco Laurana (c.1430–1502)

Desiderio da Settignano (c.1430–1464)

Andrea della Robbia (1435–1525)

Niccolò dell'Arca (c.1435/1440–1494)

Benedetto da Maiano (1442–1497)

Giovanni Antonio Amadeo (c.1447–1522)

Tullio Lombardo (1460–1532)

Andrea Sansovino (c.1467–1529)

Pietro Torrigiano (1472–1528)

Michelangelo (1475–1564)

Bartolommeo Bandinelli (1493–1560)

Benvenuto Cellini (1500–1571)

Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli (c.1506–1563)

Leone Leoni (1509–1590)

Bartolomeo Ammanati (1511–1592)

Alessandro Vittoria (1525–1608)

Giambologna (1529–1608)

Vincenzo Danti (1530–1576)

Stefano Maderno (c.1576–1636)

Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680)

Giovanni Battista Foggini (1652–1725)

Giuseppe Sanmartino (1720–1793)

Antonio Canova (1757–1822)

Lorenzo Bartolini (1777–1850)

Vincenzo Gemito (1852–1929)

Umberto Boccioni (1882–1916)

Arturo Martini (1889–1947)

Marino Marini (1901–1980)

Giacomo Manzù (1908–1991)

Silvio Gazzaniga (1921-)

Arnaldo Pomodoro (1926-)

French bronze

Patinated and ormolu Empire timepiece representing Mars and Venus, an allegory of the wedding of Napoleon I and Archduchess Marie Louise of Austria in 1810. By the famous bronzier Pierre-Philippe Thomire, ca. 1810.

The Candelabro Trivulzio in the Milan Cathedral, a seven-branch bronze candlestick measuring 5 meters in height, has a base and lower part decorated with intricately designed ornament which is considered by many to be French work of the 13th century; the upper part with the branches was added in the second half of the 16th century. A portion of a similar object showing the same intricate decoration existed formerly at Reims, but was unfortunately destroyed during World War I.

In the 16th century the names of Germain Pilon and Jean Goujon are sufficient evidence of the ability to work in bronze. A great outburst of artistic energy is seen from the beginning of the 17th century, when works in ormolu or gilt bronze were produced in huge quantities. The craftsmanship is magnificent and of the highest quality, the designs at first refined and symmetrical; but later, under the influence of the rococo style, introduced in 1723, aiming only at gorgeous magnificence. It was all in keeping with the spirit of the age, and in their own sumptuous setting these fine candelabra, sconces, vases, clocks and rich mountings of furniture are entirely harmonious. The "ciseleur" and the "fondeur", such as Pierre Gouthière and Jacques Caffieri, associated themselves with the makers of fine furniture and of delicate Sèvres porcelain, the result being extreme richness and handsome effect. The style was succeeded after the French Revolution by a stiff, classical manner which, although having a charm of its own, lacks the life and freedom of earlier work. In London the styles may be studied in the Wallace collection, Manchester Square, and at the Victoria and Albert Museum, South Kensington; in New York at the Metropolitan Museum.

French Sculptors;

Pierre Bontemps (c.1505-1568)

Jean Goujon (c.1510-1565)

Jean Juste (c.1515-1530)

Pierre Lescot (c.1515-1578)

Germain Pilon (c.1535-1590)

Barthélemy Prieur (c.1536-1611)

Antoine Coysevox (1640-1720)

Nicolas Coustou (1658–1733)

Antoine Coypel (1661–1722)

Louis-François Roubiliac (1702–1762)

Jean-Baptiste Lemoyne (1704–1778)

Jean-Baptiste Pigalle (1714–1785)

Etienne-Maurice Falconet (1716–1791)

Jean-Baptiste Defernex (1729–1783)

Jean Antoine Houdon (1741–1828)

François Rude (1784–1855)

Antoine-Louis Barye (1795–1875)

Auguste Préault (1809–1879)

Eugène André Oudiné (1810–1875)

Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse (1824–1887)

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux (1827–1875)

Edgar Degas (1834–1917)

Auguste Rodin (1840–1917)

Jean Antonin Mercié (1845–1916)

Paul Gauguin (1848–1903)

Antoine Bourdelle (1861–1929)

Aristide Maillol (1861–1944)

Georges Lacombe (1868–1916)

Constantin Brâncuși (1876–1957)

Raymond Duchamp-Villon (1876–1918)

Jean (Hans) Arp (1886–1966)

Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968)

Ossip Zadkine (1890–1967)

Jacques Lipchitz (1891–1973)

Max Ernst (1891–1976)

Georges Gimel (1898–1962)

Alberto Giacometti (1901–1966)

Hans Bellmer (1902–1975)

Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010)

Etienne Martin (1913–1995)

Constantine Andreou (1917–2007)

César Baldaccini (1921–1998)

Jean Tinguely (1925–1991)

Armand Fernandez (1928–2005)

Niki de Saint-Phalle (1930–2002)

Jules Michel (1931–)

Jean-Michel Sanejouand (1934–)

Daniel Buren (1938–)

Andrey Lekarski (1940–)

Christian Boltanski (1944–)

Jean-Yves Lechevallier (1946-)

Gérard Garouste (1946–)

Pierre Toutain-Dorbec (1951–)

Jean-Marc Bustamante (1952–)

Jean Paul Leon (1955–)

Pascale Fournier (1951–)

Patrick Moya (1955–)

Michel De Caso (1956–)

Amelie Chabannes (1974–)

Abdelkader Benchamma (1975–)

English bronze

Casting in bronze reached high perfection in England, where a number of monuments yet remain. William Torel, goldsmith and citizen of London, made a bronze effigy og Henry III, and later that of Queen Eleanor for their tombs in Westminster Abbey; the effigy of Edward III was probably the work of one of his pupils. No bronze fonts are found in English churches, but a number of processional crucifixes have survived from the 15th century, all following the same design and of crude execution. Sanctuary rings or knockers exist at Norwich, Gloucester and elsewhere; the most remarkable is that on the north door of the nave of Durham Cathedral which has sufficient character of its own to differentiate it from its Continental brothers and to suggest a Northern origin. The Gloucester Candlestick in the Victoria and Albert Museum in South Kensington, displays the power and imagination of the designer as well as an extraordinary manipulative skill on the part of the founder. According to an inscription on the object, this candlestick, which stands some 2 ft (61 cm) high and is made of an alloy allied to bronze, was made for Abbot Peter who ruled from 1109 to 1112. While the outline is carefully preserved, the ornament consists of a mass of figures of monsters, birds and men, mixed and intertwined to the verge of confusion. As a piece of casting it is a triumph of technical ability. For secular use the mortar was one of the commonest of objects in England as on the Continent; early examples of Gothic design are of great beauty. In later examples a mixture of styles is found in the bands of Gothic and Renaissance ornament, which are freely used in combination. Bronze ewers must have been common; of the more ornate kind two may be seen, one at South Kensington and a second at the British Museum. These are large vessels of about 2 ft (61 cm) in height, with shields of arms and inscriptions in bell-founders' lettering. Many objects for domestic use, such as mortars, skillets, etc., were produced in later centuries.

European brass and bronze

This section is not concerned with sculpture in bronze, but rather with the many artistic applications of the metal in connection with architecture, or with objects for ecclesiastical and domestic use. Why bronze was preferred in Italy, iron in Spain and Germany and brass in the Low Countries cannot be satisfactorily determined; national temperamente is impressed on the choice of metals and also on the methods of working them. Centres of artistic energy shift from one place to another owing to wars, conquests or migrations.

Leaving alone remote antiquity and starting with Imperial Rome, the working of bronze, inspired probably by conquered Greece, is clearly seen. There are ancient bronze doors in the Temple of Romulus in the Roman Forum; others from the baths of Caracalla are in the Lateran Basilica, which also contains four fine gilt bronze fluted columns of the Corinthian order. The Naples Museum contains a large collection of domestic utensils of bronze, recovered from the buried towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum, which show a high degree of perfection in the working of the metal, as well as a wide application of its use. A number of moorings in the form of finely modelled animal heads, made in the 1st century AD, and recovered from Lake Nemi in the Alban hills some years ago, show a further acquaintance with the skilful working of this metal. The throne of Dagobert in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, appears to be a Roman bronze curule chair, with back and part of the arms added by the Abbot Suger in the 12th century.

Byzantium, from the time when Constantine made it the seat of empire, in the early part of the 4th century, was for 1,000 years renowned for its works in metal. Its position as a trade centre between East and West attracted all the finest work provided by the artistic skills of craftsmen from Syria, Egypt, Persia, Asia Minor and the northern shores of the Black Sea, and for 400 years, until the beginning of the Iconoclastic period in the first half of the 8th century, its output was enormous. Several Italian churches still retain bronze doors cast in Constantinople in the later days of the Eastern Empire, such as those presented by the members of the Pantaleone family, in the latter half of the 11th century, to the churches at Amalfi, Monte Cassino, Atrani and Monte Gargano. Similar doors are at Salerno; and St Mark's, Venice, also has doors of Greek origin.

The period of the Iconoclasts fortunately synchronised with the reign of Charlemagne, whose power was felt throughout western Europe. The craftsmen who were forced to leave Byzantium were welcomed by him in his capitals of Cologne and Aix-la-Chapelle and their influence was also felt in France. Another stream passed by way of the Mediterranean to Italy, where the old classical art had decayed owing to the many national calamities, and here it brought about a revival. In the Rhineland the terms "Rhenish-Byzantine" and "Romanesque" applied to architecture and works of art generally, testify to the provenance of the style of this and the succeeding period. The bronze doors of the Cathedral of Aix-la-Chapelle are of classic design and date probably from Charlemagne's time. All through the Middle Ages the use of bronze continued on a great scale, particularly in the 11th and 12th centuries. Bernward, bishop of Hildesheim, a great patron of the arts, had bronze doors, the Bernward Doors, made for St Nicholas' church (afterwards removed to the cathedral) which were set up in 1015; great doors were made for Augsburg somewhere between 1060 and 1065, and for Mainz shortly after the year 1000. A prominent feature on several of these doors is seen in finely modelled lion jaws, with conventional manes and with ring hanging from their jaws. These have their counterpart in France and Scandinavia as well as in England, where they are represented by the so-called Sanctuary Knocker at Durham Cathedral.

Provision of elaborate tomb monuments and of church furniture gave much work to the German founder, the former largely in the nature of sculpture. Mention may be made of the seven-branch candlestick at Essen Cathedral made for the Abbess Matilda about the year 1000, and another at Brunswick completed in 1223; also of the remarkable font of the 13th century made for Hildesheim Cathedral at the charge of Wilbernus, a canon of the cathedral. Other fonts are found at Brandenburg and Würzburg. Of smaller objects such as ewers, holy-water vessels, reliquaries and candelabra, a vast number were produced. Most of the finest work of the 15th century was executed for the Church.

The end of the Gothic period in Germany found the great craftsman, Peter Vischer of Nuremberg, and his sons, working on the bronze shrine to contain the reliquary of Saint Sebald, a finely conceived monument of architectural form, with rich details of ornament and figures; among the latter appearing the artist in his working dress. The shrine was completed and set up in the year 1516. This great craftsman executed other fine works at Magdeburg, Römhild and Breslau. Reference should be made to the colossal monument at Innsbruck, the tomb of the Emperor Maximilian I, with its 28 bronze statues of more than life size. Large fountains in which bronze was freely employed were set up, such as those at Munich and Augsburg. The tendency was to use this metal for large works of an architectural or sculpturesque nature; while at the same time smaller objects were produced for domestic purposes.

Bronze articles are always present in Fine Furnishings and Decorated Arts auctions at Centurion Auctioneers which are held regularly.

Click on the images for more information.

Should you have any questions in regards to Bronze articles that you might wish to evaluate or to list in future auctions, please visit the CONTACT page , the VALUATIONS page or the REQUEST INFORMATION page or send an email to Centurion Auctioneers - info@centurion-auctions.com

CAST FROM A MODEL BY HENRI-ALFRED-MARIE JACQUEMART (1824-1896), LAST QUARTER 19TH CENTURY

6 ¼ in. (16 cm.) high

Sold $12,500 Christie's auctions

CAST BY DE BRAUX D'ANGLURE, FROM THE MODEL BY BARON CARLO MAROCHETTI (1805-1867), PARIS, SECOND HALF 19TH CENTURY

32 ¼ in. (82 cm.) high; 22 in. (56 cm.) wide; 10 7/8 in. (26.5 cm.) deep

Sold £12,500 Christie's auctions

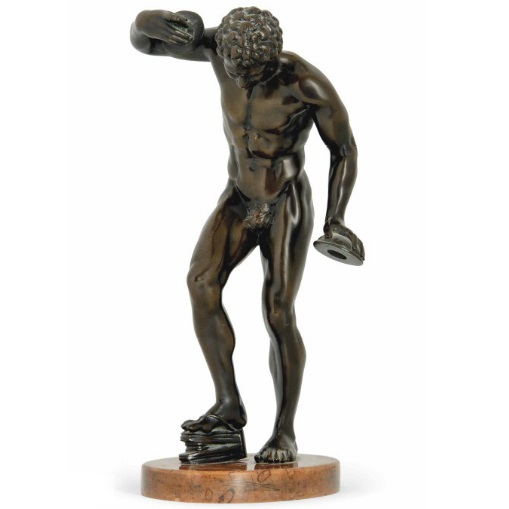

AFTER THE ANTIQUE, LATE 19TH CENTURY

12 ½ in. (32 cm.) high

Sold £1,188 Christie's auctions

EARLY 20TH CENTURY

28 ½ in. (72.5 cm.) high

Sold £1,875 Christie's auctions

BY ADRIAEN DE VRIES (DIED 1626), 1626

43 in. (109 cm) high

Sold $27,885,000 Christie's auctions

BY JOS KORSCHGEN (1876-1937)

18 1/2 in. (47 cm.) high; 31 in. (79 cm.) wide; 8 3/4 in. (22 cm.) deep

Sold £3,500 Christie's auctions

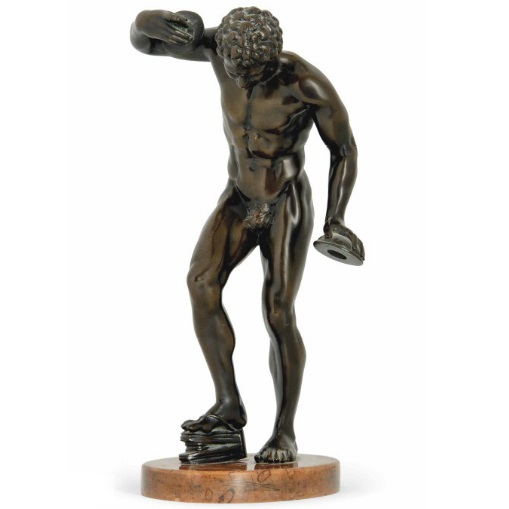

AFTER THE MODEL BY GIAMBOLOGNA, LATE 19TH CENTURY

70 ½ in. (179 cm.) high; 19 ½ in. (49.5 cm.) wide; 38 ½ in. (98 cm.) deep

Sold £21,250 Christie's auctions

17TH CENTURY

9 ¼ in. (23.5 cm.) high; 10 in. (26 cm.) diameter

Sold £2,250 Christie's auctions

AFTER THE ANTIQUE, ITALIAN, LATE 16TH OR EARLY 17TH CENTURY

15 in. (38.1 cm.) high

Sold $35,000 Christie's auctions

SIR WILLIAM HAMO THORNYCROFT, R.A. (1850-1925)

7 ¾ in. (20 cm.), high

Sold £13,750 Christie's auctions

FREDERIC, LORD LEIGHTON, P.R.A., R.W.S. (1830-1896)

20 ¾ in. (52.5 cm.) high

Sold £32,500 Christie's auctions

CAST FROM THE MODEL BY ENRIC CASANOVAS (1882-1948), CIRCA 1930

15 ¾ in. (40 cm.) high, overall

Sold £1,625 Christie's auctions